PRIOR to Saturday’s home match against Aberdeen, Lisbon Lion Celtic captain Billy McNeill opened a new entrance to Paradise: The Celtic Way.

The response from supporters was overwhelmingly positive as many gathered before and after the game to see the impressive new face of Celtic Park.

You now feel like you are entering the grounds of a European football giant. The experience as you exit London Road leaving behind the impressive Emirates Arena constructed for the Commonwealth Games to take in the new panoramic vista of Celtic Park is one that supporters will savour for years to come.

The Road to Paradise is changing and so is the social history of the east end. In the shadows of Celtic Park is the Bellgrove Hotel, a notorious marker amid the Celtic bars dotted along the Green Mile.

In the spirit of regeneration it’s worth considering the slum conditions that vulnerable, ill and addicted men are living under there. Journalist and Celtic supporter Kevin McKenna described it as “the evil that is allowed to flourish on Glasgow’s Gallowgate".

In a recent article he wrote: “This hellhole has a staff of two, presumably to keep the costs down. For the Bellgrove is a privately-run facility that rakes in several million pounds a year for the two city property magnates who own it.

"They make their money from the housing benefit these men receive each fortnight. Basically, the state hands over millions of pounds every year to this pair to keep its most embarrassing citizens away from polite society.”

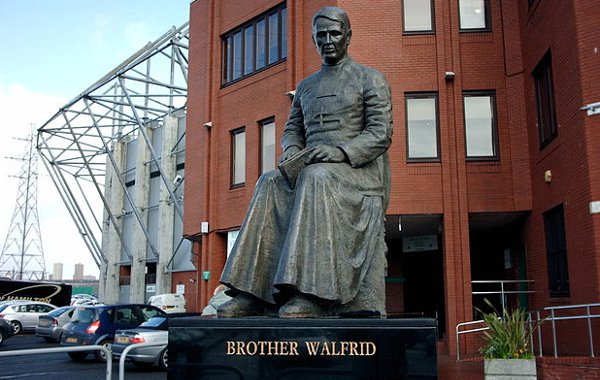

Celtic founder Brother Walfrid

Celtic founder Brother WalfridWithin clear view on The Celtic Way are two Glasgow tower blocks known as the Gallowgate Twins (the Whitevale and Bluevale towers). These two relics suggest a bygone age of public housing and feature in a recent documentary Round Ma Bit: The Gallowgate Twins.

Film-maker and presenter Liam Young quite literally considers another perspective on what regeneration means to the community around the east end, it’s a stirring presentation that Celtic supporters who care about the social fabric of the club should consider watching.

He visits Celtic Park and in the context of the surrounding environment it’s a thought-provoking juxtaposition especially when talking to one of the last remaining residents from the disconcerting heights of the towers, Willie McGonigle.

As he looks out onto Paradise, Willie has mixed feelings about leaving what he regards as home. Three years ago Margaret Jaconelli was displaced from her red sandstone tenement home of 34 years after being served with a compulsory purchase order.

She was removed by police and sheriff officers at 5am and the gruelling eviction lasted for two hours. She can no longer afford to live in the area’s newly-built housing. University of Glasgow researcher Neil Gray suggests the purchase orders are implemented to remove people “who don’t have access to lawyers and lots of funds.”

He adds that outgoing residents “don’t have the ability to fight against [the orders] or reclaim the value of their homes where large scale property developers are making a lot of money out of the process.”

Today outside Paradise the club crest on Celtic Way represents a new meeting place. A different social history will develop around this fresh marker as it did the day social reformer Michael Davitt laid the first sod of turf on the sight of the then new “Holy Ground” in 1892.

A coffee shop and museum are also part of the plan for a regenerated Celtic Park. Beyond the aesthetics, profit and entertainment Brother Walfrid birthed Celtic to assist a cause: social justice. Driven by his faith and conscience Celtic was created to aid the poverty and desperation around the east end.

As the classical composer James MacMillan once pointed out gospel values are essential to the unique character of Celtic and they continue to represent many fans of the club. What would Brother Walfrid make of the men left to die in the Bellgrove Hotel or people without means to stand up against an ancient law that unfairly displaces ordinary people from their home and community?

What would he make of community centres being closed to make way for a temporary car-park to be used for the Commonwealth Games? It is likely Andrew Kerins would take us back to the value of “whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.”

One thing is certain, wherever he saw injustice and inequality he would utilise the club to be a compassionate voice and an agent for change in our society, he would make the most of Celtic to support the poorest and most disempowered.

He would tend to the broken and help them realise their potential. He would respect the dignity of every human life in the community around him and realise the potential for transformation not just in bricks and mortar but in human life.

Beyond the “more than a club” sentiment and the value of entertaining Celtic should always stand as a beacon for the reason it was created in the first place.

Richard Purden is the author of We Are Celtic Supporters and Faithful Through and Through